One of the first opera DVDs my family and I bought after the opera obsession started was the 2013 Vienna production of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West, with Jonas Kaufmann and Nina Stemme. (Perhaps because it was one of the less pricey among other Jonas DVDs, and also because Nina was in it too.) None of us had any familiarity with the opera. After all, we, like many, when thinking of Puccini, thought of Turandot, La Bohème, and Madama Butterfly. Perhaps Manon Lescaut. La Fanciulla del West seems to be ranked somewhere in the “lesser works,” if we were to judge by what strikes this newbie as its relative neglect. Anyhow, this will be another “thematic” post, on an opera that grows on me daily…and anyone reading this has any recommendations for recordings that are available, or written works about this opera, I’d be very grateful!

(Note: spoilers ahead. Also note: the translations I use below–aside from my own parenthetical notes, as well as the “ch’ella mi creda libero”–are those of Bill Parker in the libretto for the CD recording of the 1956 La Scala production with Corelli, Gobbi, and Frazzoni, copyright 2007 by Allegro Corp.)

A Synopsis…

The story of La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the West, based on the stage play The Girl of the Golden West by David Belasco) is set in 1849-1850 “Gold Rush” California, in a mining camp, opening in the Polka Saloon where Minnie—idolized by all of the miners and sought after most avidly by the Sheriff of the town, Jack Rance—works, as well as has her little “academy” for the miners, reading to them and teaching them about Scripture (though she feels her own education has been sadly neglected). Ashby, a Wells Fargo agent, enters the scene, having tracked the bandit Ramerrez and his thieving gang for the past three months, and having a lead from Ramerrez’ supposed lover, Nina Micheltorena, that Ramerrez is nearby. Meanwhile, a stranger—whom Minnie has met once before—enters the saloon under the name of “Johnson,” and love begins to blossom between Minnie—who has as yet managed to escape being so much as kissed, in spite of growing up amongst men who all adore her—and the stranger. In Act II, Johnson visits Minnie at her home up in the mountains. (Again, the words “lontano”–distant, far away—are used in relation to Minnie’s dwelling.) Johnson “steals” her first kiss—but shortly after, Rance and his men, having followed the trail to her house, question Minnie about Johnson’s whereabouts—while he remains hidden—and, before they leave, reveal to her that the one she knows of as “Johnson” is actually the bandit Ramerrez. She feels betrayed and sends Johnson out into the snowy night; Johnson becomes wounded, and only eludes capture when Rance returns to Minnie’s home by losing to a game of poker which Minnie has proposed (and cheated on—an echo and contrast to the original “justice” shown the cheater at cards in Act I): if he wins, Rance can take both her, and Johnson; if Rance loses, he has to let Johnson go—who will then belong to Minnie. Act III sees the bandit ready to hang; he is then again saved—in more ways than one—by Minnie. They fulfill the dream that has been a constant throughout the ups and downs of their relationship: to go away, to a far distant land (“lontano”).

“La Fanciulla” as parable; a “far away” sensibility

In my first encounter, I was often moved, and particularly in moments such as the Act III aria, “Ch’ella mi creda libero e lontano”–“Let her believe that I’m free and far away,”–which has become my favorite Puccini aria. But except for such moments and the beauty of the performances of the two leads in the Vienna production–no one breaks the heart like Jonas and Nina, and in my last viewing of it I was sobbing in Act I–it wasn’t entirely love at first encounter with the opera itself. I no doubt smiled, perhaps even laughed, at first hearing the stereotyped names, and the “Americanisms,” from the “Hello, hello!” chorus in the opening, to “Whiskey per tutti!” (It’s a stereotype, perhaps, that Italians are in love with Western Americana, but I’m sure there’s something to it, as film Westerns à la Sergio Leone have been referred to as “spaghetti Westerns.” Though, I daresay, few are in love with anything American at this moment–okay, political dig over for this post.) But, somehow, as we get further into the opera, we’re swept away, not unlike the miners in the story hearing the distant ballad of Jack Wallace, pining for their own homeland and their own families; there is in us too a kind of nostalgia for a lost time, or sensibility.

It is a sensibility that is distant, far away (“lontano”), like the memories of home, or childhood, or, perhaps, the hope of redemption.

Such sensibilities are familiar to me not only from my lifelong love of Dickens, but—more applicable here—to a time, years back, when I was delving into reading Victorian and Edwardian stage melodramas, replete with sentiment, outrageous plots, and “unlikely” lead characters. In Fanciulla, which was based on the stage play by David Belasco, The Girl of the Golden West, we have a bandit-with-a-heart-of-gold (Dick Johnson, aka Ramerrez), and a rougher Little Dorrit-type in Minnie, who seems somehow as miraculously pure and unaffected by her somewhat unsavory surroundings—not only that, but making the most of them and raising those around her—as the quieter Dickensian heroine.

Certain “grand,” sentimental, or sacrificial themes that were popular in stage melodrama, as well as the type of character who, like Minnie, is innocent and pure in the midst of rough surroundings, went somewhat out of fashion post-World War I, when much of the “romance” of self-sacrifice had been marred by the brutality and horror of war. My favorite Dickens novel, ever popular but not necessarily considered critically on the level of Bleak House or Great Expectations, is A Tale of Two Cities, and various adaptations of it, including Sir John Martin-Harvey’s The Only Way (he played Carton on and off the stage for nearly 40 years) were popular around the turn of the century…less so two decades later. The world had fallen into a different mood. Much like A Tale in one respect, La Fanciulla might be taken more as a “parable”–or rather, a parable of a parable–set against a dramatic historical backdrop, than as anything like realistic historical fiction. If A Tale might be said to be a parable of the 11th hour worker or the prodigal son, illustrated by John 11:25 as referenced in the novel, Fanciulla might well reflect the parable of the lost sheep, or the message in Psalm 51 that Minnie reads to the miners in Act I (more below). We might say, too, that Rance is a kind of representation of “justice” (though we know there are personal motives in his hatred of Johnson as well) in contrast to the “mercy” of Minnie, who, like God himself, loves the sinner, the lost. The Act II finale card game between Minnie and Rance—and yes, in what other opera are we going to find that a game of poker decides the fate of the heroes?–is a kind of battle for this wounded (lost) soul, much the way, in Hugo’s Les Misérables, Valjean and Javert (Mercy vs. Justice) are battling over Fantine, the woman driven to heartbreaking prostitution and poverty, when Javert is ready to throw her in prison–regardless of the fate of Fantine’s daughter, much less her own health. (The “allegorical” aspect is much more pronounced in the novel than is usually portrayed on film.) These are all personal conjectures, and we can make out from the story any number of things…that’s the beauty of story.

So, whatever my relationship with Fanciulla was at the outset, this opera has grown on me over time, and attached itself to me inextricably. I am almost tempted to say it is my favorite Puccini overall—if we are looking at an opera as a whole, because it’s frankly impossible to beat Act I of Turandot, the Act I finale of Tosca, or innumerable other sequences and arias from “E lucevan le stelle” to “Nessun dorma”–nor do we have as compelling a villain as Scarpia.

But in Fanciulla, I am more and more struck by a special kind of consistency and unity in the themes and orchestration; the sound itself which is something entirely unique. (Except that many a film composer has stolen blindly from it since, in my opinion–having grown up watching movies, John Ford and Sergio Leone included.) I don’t know how to put my finger on it, but Puccini has managed to capture the “Western” sound as we now associate it with the Western film…and this, in an opera which premiered in 1910! (It premiered at the Metropolitan opera, conducted by Arturo Toscanini, with Enrico Caruso as Johnson.) I sometimes wonder: Did Puccini help invent what we “hear” when we recall “Western” film scores?

Themes/Motifs

And not only an overall consistency of sound and motif, but Puccini has nailed the music-theme-echoing-the-subject’s-theme in some mysterious way which I’ll try to give a few examples of, as I heard—or felt—them, using names that I associate with each. (I may well need correction by those who are more experienced with this opera.) I’ll use this youtube version of the whole 2013 Vienna production–regretfully, there are no English subtitles in the YT version–as a point of reference for the time tags in my comments below:

1. The “lontano”/“far away, distant” theme (nostalgic, looking back)

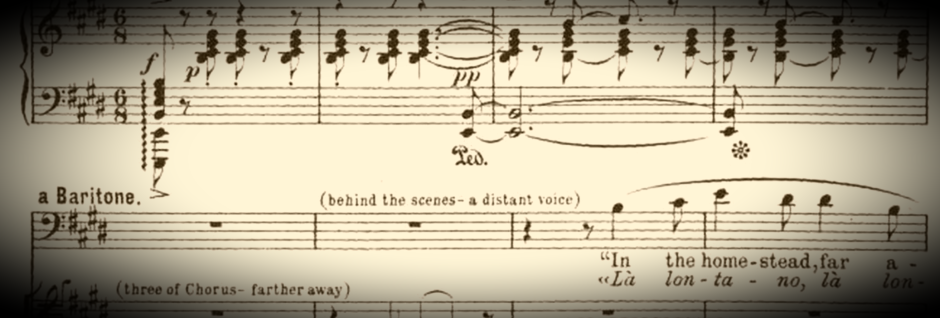

Of course, the overture gives us an overview of some of the main themes. After that, what I call the “lontano theme” in the Jack Wallace ballad that is echoed again at certain key moments. There is something about the genre of the “Western” that calls out for this kind of nostalgia…first heard in the above video (from a distance) at 6:54.

I have also since learned that “lontano” is also a musical term, meaning “distant,” or “far away.”

2. Minnie’s theme/savior theme

Of course, “Minnie’s theme” is evident (heard in the above at about 18:13): she has one of the grand entrances in opera. It was, for me, one weakness of the Vienna production, that it didn’t make the most of her entrance, especially with a Minnie as stellar as Nina Stemme! The Met-on-Demand version from 1992, with Placido Domingo, Barbara Daniels, and a wonderfully slick and threatening Sherrill Milnes, does this better. (And I generally liked the set/production better in the 1992 version as well, though I far prefer the singing/acting/interpretation of the two leads of Stemme/Kaufmann over any I’ve yet seen or heard.) The production that really hits the nail on the head with Minnie’s entrance is the the La Scala production from 2016, recommended by Blake, can still be seen at this link—and is a great example of an entrance (and thematically does some truly wonderful and inventive things which highlight the nostalgia for the Western film in a very direct hommage…if you love classic cinema, and/or specifically classic Westerns, watch at least the first 5 minutes and you’ll be hooked…). You really want her entering in silhouette, with her gun, against a sunset background…

Minnie’s theme is again repeated as a kind of “hero” theme: again, in her timely entrance in Act III, to save Johnson/Ramerrez from the rope.

3. The redemption theme/Ramerrez theme

This is one that kills me, and has one of the best payoffs of any theme, ever. We first hear a hint of it (after the overture) around 23:55 as Minnie explains the meaning of Psalm 51 to the miners:

“Wash me and I shall be white as snow.

Create in my breast a pure heart, and renew within me an elect spirit…”

(My note: enter “redemption theme” here:)

That means, boys, there’s no sinner in the whole world

to whom the way of redemption is not open…

The “lontano” theme comes back again here too.

The redemption theme comes back as Johnson’s initial goal—robbing the Polka saloon of their gold—begins to slip away through the influence of Minnie, and he finally declares his help: “No one would dare to touch the gold.”

But in each repetition, the redemption theme is not quite “resolved”; the theme drifts away before it can come to a satisfying conclusion—until, that is, one of the best payoffs in any opera: Johnson’s identity aria in Act II, where he tells his story and admits to being the bandit Ramerrez. (And again, in another way, at the very end of the opera–when all of these themes are woven together.) In this version, the whole “story” aria is from about 1:24:15-1:27:38, but the “redemption theme” comes in at the words about how he began to pray to God not to let her know his true identity: 1:26:44-1:27:38.

Just a word! I won’t defend myself: I’m a thief! I know, I know!

But I wouldn’t have robbed you! I am Ramerrez; born a vagabond,

“Thief” was my name from the day I came into the world.

But I never knew it while my father was living.

It’s been six months since my father died…

The only wealth he left me, to care for my mother and brothers,

was his paternal legacy: a gang of common thieves! I had to accept it.

That was my destiny! But one day I met you.

I dreamed of going far away with you, (my note: again, “lontano”),

redeeming everything with a life of work and love.

(my note: enter “redemption theme…)

My lips murmured a fervent prayer: Oh God!

Let her never know of my shame!

Alas! The dream was in vain! Now, I’m finished…

4. Another “lontano” theme (forward-looking, future-oriented)

One of my favorite themes, but which is never quite resolved in the way that I somehow wish it to be—but it is somehow achingly perfect—is a theme introduced in Act II, when, after again pointing out that Minnie’s home itself is “far away” from the world, and where one “can feel God’s presence”, she talks about her “academy,” and that she herself is the teacher. (See 1:08:38 in the above.) This theme comes in several times in this tender scene in Minnie’s home (particularly 1:14:00 to 1:15:14), climaxing in the moment when they sing together (1:14:23): “Dolce vivere e morir, e non lasciarci più”/“So sweet to live and die and never again to part”.

Afterthoughts: “Ch’ella mi creda libero e lontano…”

The above themes are just a few of my favorites that I wanted to make special mention of. This may be the first of many discussions of La Fanciulla, as I’m about to read the Belasco stage play on which this opera was based, and perhaps eventually get around to his novelized version of it, free via Google books.

But I can’t leave off a first discussion of this opera without bringing in a sample of my favorite Puccini aria, “Ch’ella mi creda libero.” Here again, the word “lontano.” (I wonder how often that word is repeated in the libretto?) Johnson’s only request before death is that they allow Minnie to believe that he is “free and far away, on a new path of redemption”; the “lontano” that is a motif both forward and backward-looking in this opera, seems to signify a new life, freedom; a new path; redemption; a pilgrimage to a distant land. Something lost, something found. How ironic that so much of what we think of as the romantic “West” (more myth than tangible reality) is the notion of “going West” itself; towards the horizon. Here, in Fanciulla, they are already “West”; the distant land they are looking for is more the interior transformation than a geographical “West.”

This version (which may not be viewable in certain countries…in which case you can see a shortened, too-hastily cut-off version here), is one that I play over and over again, and although the “Ch’ella mi creda” doesn’t begin until halfway through, it is worth listening to from the beginning–“Risparmiate lo scherno”/”Spare me your sneers” etc, and especially the soaring notes just before “Ch’ella mi creda libero,” translated here:

Let her believe that I’m free and far away,

upon a new path of redemption!

She’ll wait for my return

and the days will pass,

and the days will pass,

and I will not, no, I will not return…

Minnie, you’re the only flower of my life,

Minnie, who has loved me so much!–So much!

Ah! You’re the only flower of my life!

Hi!!!! What a wonderful explenation of “Fanciulla”!!!you catch every nuance,beautifull bautifull, and being one of my favorites, I appriciate very much!!! Thanks thanks! !!!!Continue this wonderfull obsession dear Rachel!!!love 💖💖💖💖💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh thank you dear Rosaria!!! That means so much to me. Glad you enjoyed it…this obsession of ours is totally delightful! One of my favorites too 💚💙💜

LikeLike

What a wonderful close reading of the opera. I’ve always loved Fanciulla (of course I love Edgar too!) and your exegesis is just brilliant. I love the details you go into and will soon spend an afternoon listing to this and reading your notations at the same time. Brava, Signorina Rachel, Brava!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for this beautiful comment!! I truly appreciate it…I do love delving a little into the themes…in terms of both music and subject 🙂 …I have yet to see an Edgar! Do you have a certain version that you especially like? Thanks again for your comment. Enjoy Fanciulla!!

LikeLike

I love your stuff! 🙂 Thanks…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Augustus, I so appreciate that!! Thank you so much 🙂 and I am so glad you are reading and enjoying these posts!

LikeLike